This is the script from a talk I gave at the Museum of London

You can watch a vide of the talk here: https://www.gresham.ac.uk/lectures-and-events/ai-education-reality-potential

While I was enjoying my morning latte on the tube earlier this month, I spotted this headline in the New Scientist: AI achieves its best ever mark on a set of English exam questions: i.e. the knowledge-based curriculum and exams. This is significant in three important ways, and these are also the three ways that I want to discuss AI and education with you this evening.

Firstly, it demonstrates the power of the AI that we can build to learn and to teach what we currently value in our education systems. This speaks to my first point that will be about the way AI can support teaching and learning.

Secondly, if this is headline news, then it demonstrates that we do not know enough about AI, because passing an exam is a very AI type problem to solve, and we should not be surprised that AI can do this. It should be something we take for granted, because we all understand enough about AI to know the basics of what it can and cannot achieve.

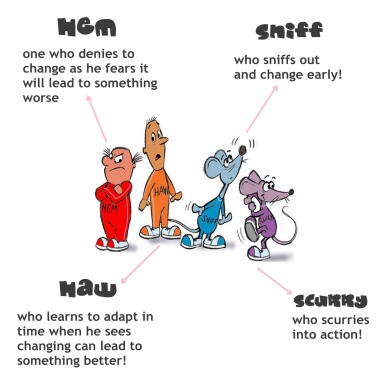

Thirdly, this headline draws our attention to the fact that we can build AI that can achieve what we set our students to achieve. The AI will get better and faster at this and it therefore is not intelligent to continue to educate humans to do what we can automate. We need to change our education systems to value our rich human intelligence. This need to change what and how we teach is also connected with the way that AI powers the automation that is changing our lives at some pace. We need very different skills, abilities and intelligences to thrive in the modern world. One only has to look at our current political failure in the UK, to see that the much-heralded education that we have provided for the last century has not provided our politicians with the emotional and social intelligence and the ability to solve problems collaboratively that the modern world requires. The need to change the what and how of teaching will be my third area for discussion tonight.

AI is empowering automation and the Fourth Industrial Revolution and its impact on education will be transformative, but what is this thing called AI?

A basic definition of AI is one that describes it as ‘technology that is capable of actions and behaviours that require intelligence when done by humans’. We may think of it as being the stuff of science-fiction, but actually it’s here and with us now from the voice-activated digital assistants that we use on our phones and in our homes, to the automatic passport gates that speed our transit through airports and the navigation apps that help us find our way around new cities and cities that we know quite well. We use AI every day, probably without giving it a thought.

The desire to create machines in our own image is not new, we have, for example, been keen on creating mechanical ‘human’ automata for centuries. However, the concept of AI was really born 63 years ago in September 1956 when 10 scientists at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire spent the summer working to create AI. If we look at the premise for this two-month study, we see that it is a premise that believes that: ‘every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it.’ And, although it seems incredibly arrogant now, the belief was that over a two-month period the team of scientists, would be able to make ‘a significant advance … in one or more of these problems.’

Following on from this there were some early successes. For example, expert systems that were used for tasks such as diagnosis in medicine. These systems were built from a series of rules through which the symptoms a patient presented with could be matched to potential diseases or causes, so enabling the doctor to make a decision about treatment. These systems were relatively successful, but they were limited because they could not learn. All of the knowledge that these expert systems could use to make decisions had to be written at the time the computer program was created. If new information was discovered about a particular disease or its symptoms, then if this was to be encompassed by the expert system it’s rule-based had to be changed. In the 1980s and 90s we had built useful systems, but certainly we were not anywhere near the dreams of the 1963 Dartmouth College conference. We plunged into what has been described as an AI winter where little significant progress was made and disappointment was felt by those who had such high expectations of what could be achieved.

Then in March 2016 came a game changing breakthrough. A breakthrough that was based on many years of research. A breakthrough that was made when Google Deepmind produced the AI system called AlphaGo that beat Lee Sedol, the world ‘Go’ champion. This was an amazing feat. A feat that could seem like magic, and whilst many of the techniques behind these machine learning algorithms are very sophisticated, these systems are not magic and they have their limitations. Smart as AlphaGo is, the real breakthrough was due to a combination that one might describe as a perfect storm. This perfect storm arises due to the combination of our ability to capture huge amounts of data, combined with the development of very sophisticated AI machine learning algorithms, plus affordable competing power and memory. These three factors when combined provide us with the ability to produce a system that could beat the world Go champion. Each of the elements in that perfect storm: the data, the sophisticated AI algorithms and the computing power and memory are important, but it is the data that has captured the imagination. And that has led to claims that ‘data is the new oil’, because it is the power behind AI and AI is a very profitable business, just like oil.

However, it’s important to remember, that just like oil, data is crude and it must be refined in order to derive its value. It must be refined by these AI algorithms. But even before the data can be processed by these algorithms it must be cleaned. So just like oil, there is a lot of work that needs to be done on the data before its value can be reaped. And even when we do reap this value from the data, it’s important to remember that machine learning is still basically just a form of pattern matching. Machine learning is certainly smart, very smart indeed, but it cannot learn everything.

AI has its limitations. For example, AI does not understand itself and struggles to explain the decisions that it makes. It has no common sense. If I ask you the audience this evening these questions: are you an empathetic friend? How well do you understand quantum physics? How are you feeling right now? Can you meditate? You will not struggle to answer, but AI would. So, the first important point to remember is that humans are intelligent in many ways. AI and Human Intelligence (HI) are not the same and the differences are extremely important, it is true that we have built our AI systems to be intelligent in the way that we perceive value in our human intelligence.

I remember in the early days of studying AI, the first grandmaster level Chess-playing Computer had been built and had beaten world champion Garry Kasparov. This seemed an amazing feat and there were people who thought that having cracked chess, which could be described as the pinnacle of human intelligence, intelligent people play chess after all. It was thought that we had cracked intelligence. And then people realised that the abilities that we take for granted, such as the ability to see, are far harder to achieve than is playing chess. Decades later, we have managed to build AI systems that can see, to an extent, but they still have their limitations.

What we need if we are to progress and grow our human intelligence, is to make sure that we recognise the need for humans to complementAI, not to mimic and repeat what the AI can do faster and more consistently than we can.

And so, what are the implications: the potential and the reality of AI within education? I believe that it is useful to think about this question from three perspectives:

1: using AI in education to tackle some of the big educational challenges;

2: educating people about AI so that they can use it safely and effectively;

3: changing education so that we focus on human intelligence and prepare people for an AI augmented world.

It is important to recognise that these three elements are not mutually exclusive. In fact, they are far from being mutually exclusive. They are interrelated in important ways.

Let us start with using AI in education to tackle some of the big educational challenges. Challenges such as the achievement gaps we see between those who achieve well educationally and those who do not. And challenges, such as those posed by learners with special and particular learning needs. If we start by looking at the reality of the systems that are available here and now, to help us tackle some of these challenges, then we will see the beginnings of the potential for the future. To start the ball rolling, I am going to handover to my friend Lewis Johnson, who runs an AI company in the US called Alelo. He can explain to you far better than I can exactly what is happening when it comes to data, AI and computing power in education.

Play video clip

Well, you heard it there from Lewis: Data has been a game changer when it comes to educational AI. And that’s true for companies working here in the UK too. If we take the London-based Century Tech, they have developed a machine learning platform that can personalise learning to the needs of individual students across curriculum areas to help them achieve their best. Their machine learning is informed by what we understand from neuroscience about the way the human brain learns. A further reality is that, in addition to being able to build intelligent platforms, such a Century, we can build intelligent tutors that can provide individual instruction to students in a specific subject area. These systems are extremely successful, not as successful as a human teacher who is teaching another human on a one-to-one basis, but the AI can, when well-designed, be as effective as a teacher teaching a whole class of students.

In addition to intelligent platforms and intelligent tutoring systems, there are many intelligent recommendation systems that can help teachers to identify the best resources for their students to use, and that help learners identify exactly what materials are most suitable for them at any particular moment in time. It is not just by learning particular areas of the curriculum that AI can make a big difference. AI can also help us to build our cognitive fitness, so that we have good executive functioning capabilities, so that we can pay attention when needed, remember what we learn and focus on what needs to be done. This system called MyCognition, for example, enables each person who uses it to complete a personal assessment of their cognitive fitness and then train themselves using a game called Aquasnap. AI helps Aquasnap to individualise training according to the needs of the particular person who is playing.

Finally, just in case you thought the reality of AI was only for adults, think again. This example from Oyalabs is a room-based monitor that can track the progress of a baby and provide that baby’s parents with individual supportive feedback to help them support their child’s development as effectively as possible.

That’s the reality of what’s available here and now when it comes to AI for education.

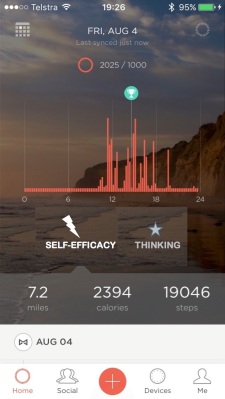

But what about the potential for the future? You’ll remember that I mentioned before that data can be described as the new oil and that it is the power behind AI. You heard Lewis talk about the way that data has been a ‘game changer’ for AI in education. And data can also be the power behind human intelligence. We can collect data in many, many ways, from our interactions with our smartphone to wearable technologies that track our heart rate, temperature, pulse, the speed of our movement and the length of our stillness. We can collect data about our interactactions with technologies in traditional ways, we can collect data passively through cameras that observe what is happening, we can collect data from technologies that are embedded in the clothes that we wear.

There are, of course, many important ethical implications associated with collecting data on this scale and these need to be addressed, but the scale of data collection is already happening and it is important to think about how this data could power education systems, not just systems designed to influence our spending or voting habits. If we accept the premise that data is the new oil and we are willing to invest the time in cleaning the data, then the final ingredient that we need to add, if we are to meet the potential that AI can bring to teaching and learning, is that we must design the AI algorithms that we use to process the data in a way that is informed by what we understand from research in the learning sciences, such as psychology, neuroscience, education. If we get this right then we can turn the sea of data that can be generated as people interact in the world into, an intelligence infrastructurethat can power all of the educational interactions of an individual.

This intelligence infrastructure can empower what we do with our smartphones, laptops, desktops, robotic interfaces, virtual and augmented reality interfaces and of course when we sit alone reading and working through books or when we interact with another person as part of our learning process. This intelligence infrastructure can tell us about how we are learning, about the process of learning, about where we are struggling and where we are excelling, based on extremely detailed data and smart algorithmic processing informed by what we understand about how people learn.

This intelligence infrastructure can also be used to power technologies to support people with disabilities and in so doing to help improve equality and social justice. We will be able to build intelligent exoskeletons, we can build intelligent glasses that can help the blind to see, and we will be able to tap in to what processing is happening in the brain allowing people to think what they want to happen on the computer screen and see it happen. But we need to remember as I highlighted earlier, that there are ethical Implications here. The potential for good is great, but unfortunately so is the potential for bad. Technologies that can be embedded in the body that can tap into the brain and bring a danger of what Noah Yuval Harare calls ‘hacking humans’.

So, what about the second implication of AI education? This implication is about educating people about artificial intelligence, so that they can use it safely and effectively. This tree diagram summarises the three key areas that I believe we need to educate people about when it comes to AI. We need everyone to have a basic understanding of AI, so that they have the skills and the abilities to work and live in an AI enhanced world. This is not coding, this is understanding why data is important to AI and what AI can and cannot achieve. We also need everyone to understand the basics of ethics, but we need a small percentage of the population to understand a great deal more about this so that they can take responsibility for the regulatory frameworks that will be necessary to try and ensure that ethical AI is what we build and use. And then there is the real technical understanding of AI that we need to build the Next Generation of AI system. Again, a small percentage of the population will need this kind of expert subject knowledge.

I would like to dwell for a moment on the ethical aspect of that tree diagram. There are many organisations exploring ethics and AI, or ethics and data. I find it useful when thinking about ethics to break down the problem into different elements. Firstly, there is the data that powers AI. Here, we need to ask questions such as: who decided that this data should be collected? Has that decision been driven by sound ethical judgement? Who knows that this data is being collected and who has given informed consent for this data to be collected and used? What is the purpose of this data collection, is it ethical.? What is the justification for collecting this data, is it sound? We must always remember that we can say no.

Next, we need to consider the processing that happens when the machine learning AI algorithms get to work. Have these algorithms been designed in a way that has been informed by a sound understanding of how humans learn? Have the AI algorithms been trained on datasets that are biased, or are they representative of the population for whom processing is being done?

And finally, there is the output – the results of the processing we have done through our AI algorithms. Is the output suitable to the audience? Is it genuine or is it fake? What’s happening when that output is received by the human interlocutor? Are we collecting more data about their reactions to this output?

There are many questions to be asked about the ethics involved in AI and education and here I have just scratched the surface, but it’s important to highlight that the ethical issues are extremely important. This is the reason I co-founded the Institute for Ethical AI and Education, because we believe that it’s an area that needs far more intention. We will be working towards the design of regulatory frameworks, BUT it’s important to remember that education will always be crucial, because regulation will never be enough on its own. We simply cannot keep up with those who want to do harm through the use of AI. We must therefore ensure that everyone is educated enough to keep themselves safe.

Finally, we come to the third category of implications from AI and education: changing education so that we can focus on human intelligence and prepare people for an AI world.

Many people, including the World Education Forum are telling us that we are now entering the Fourth Industrial Revolution – the time when many factors across the globe, including the way that AI is powering workplace automation, are changing the workplace and our lives for ever. There is much media attention to this Fourth Industrial Revolution with some coverage making such positive predictions as these from Australia that suggest that we will have two hours more time each week, because some of the more tedious aspects of our jobs will be automated. Our workplaces will be safer, and jobs will be more satisfying as we learn more.

Not everyone is as optimistic and there are an increasing number of reports that consider the consequences for jobs of the increased automation taking place in the workplace. This is an example from a report called ‘Will robots really steal our jobs’ published in 2018 by PWC. We can see from this graph from the report that transportation and storage appear to be the areas of the economy where most job losses will occur. Education will be the least prone to automation. We could interpret that as meaning that education will not change. However, I believe that education will change dramatically. It will change as we use more AI and it will change as what we need to teach changes in order to ensure that our students can prosper in an AI augmented world. And if we look at the second chart, it is perfectly clear that the impact will not be felt by everyone equally. Of course, those with higher education levels will be least vulnerable when it comes to automation and job loss. We therefore need to provide particular support for those with lower levels of education.

Personally, I do not think all these reports are that useful, interesting as they are. As a race, we humans are rather poor at prediction and the differences of opinion across the different reports indicates the complexity of predicting anything in such fast-changing circumstances. Trying to work out what to do for the best in a changing world, is a little bit like driving a car in dense fog along a road that you don’t know. In these circumstances, a map about the road ahead has limited use. What we really need is to know that we have a car that is well-equipped, we have brakes that work, lights that work. We want to be warm and we want to know that as a driver, we understand how to operate the car, that we understand the rules of the road, that we have eyesight that’s good enough to help us to see in the limited visibility ahead and that we can hear what is going on so that you can spot any impending dangers if they are indicating their presence by being noisy. A huge truck thundering towards us, for example.

So, what’s the equivalent of this good car and good driver when it comes to what we need in order to find our way through the fog of uncertainty around the Fourth Industrial Revolution?This is a subject that I have studied and written about quite a lot and a subject that is covered in this book: Machine Learning and Human intelligence: the future of education 21stcentury. Here I can only skim over the way that I unpack the intelligence that we need humans to develop if we are to find our way through this foggy landscape. This is the intelligence that can help us to cope with the uncertainty and it can help us to differentiate ourselves from AI systems. This is an interwoven model of intelligence that has seven interacting elements:

The first element of this interwoven intelligence is: interdisciplinary academic intelligence. This is the stuff that is part of many education systems at the moment. However, rather than considering it through individual subject areas as we do now, we need to consider it in an interdisciplinary manner. Complex problems are rarely solved through single disciplinary expertise, they require multiple experts to work together. The world is now full of complex problems and we need to educate people to be able to tackle these complex problems effectively. We therefore need to help our students see the relationships between different disciplines. We need them to be able to work with individuals who have different subject expertise and to synthesise across these disciplines to solve complex problems.

Secondly, we need to help our students understand what knowledge is, where it comes from, how we identify evidence that is sound enough to justify that we should believe that something is true. I refer to this as meta knowing,but of course we can use the terminology of epistemology and personal epistemology to describe this meta knowing.

The third elements of our intelligence that we really need to develop in very sophisticated ways is social intelligence. It is very hard for any artificially intelligent systems to achieve social intelligence, and it is fundamental to our success. Because, we need to collaborate increasingly in order to solve the kinds of complex problems that we will be faced with on a daily basis.

Fourthly, we need to develop our meta cognitive intelligence. This is the intelligence that helps us to understand what we need to know to understand how we learn, how we can control our mental processes, how we can maintain our focus and spot when our attention is skidding away from what it is we are trying to learn. These metacognitive processes are fundamental to sophisticated intelligence and they are again hard for AI to achieve.

The fifth element of intelligence we must consider is our meta emotional intelligence. This is what makes us human. We need to understand the subjective emotional experiences we sense and we need to understand the emotional perspectives of the others with whom we interact in the world. This emotional intelligence is also hard for AI. AI can simulate some of this, but it cannot actually feel and experience these emotions.

We also need to recognise the importance of our physical presence in the world and the different environments with which we interact. We as humans, are very good at working out how to interact intelligently in multiple different environments. This meta contextual intelligence is something at which we can excel, and something that AI has great trouble with. Context here means more than simply physical location it means location, it means the people with whom we interact, the resources that are available to us and the subject areas that we need to acquire and apply in order to achieve our goal.

If we can build these interwoven elements of our human intelligence then we can really achieve what’s important for the future of learning and that is: accurate perceived self-efficacy. By this I mean that we can see how we can be effective at achieving a particular goal, at identifying what that goal consists of, identifying what aspects of that goal we believe we can achieve now, what aspects we need to learn about and train ourselves to achieve. In order to be self-effective, we must understand than to apply all the elements of intelligence so that we can work across and between multiple disciplines with other people with effective control and understanding of our mental and emotional processes.

Let me take a moment to stress something important here. This is about intelligence. It is not about 21stcentury skills or so-called softskills. It is about something much more foundational than any skill or knowledge. It is about our human intelligence. I also want to emphasize that we can measure the development of our intelligence across all seven elements. They can all be measured and importantly they can all be measured in increasingly nuanced ways through the use of AI. This enhanced and continual formative assessment of our developing intelligence will shed light on aspects of intelligence and humanity that we have not been able to evidence before. We can use our AI, to help us to be more intelligent, and this is very important.

The truth of the matter is that being human is extremely important. The very aspects of our humanity, the aspects that we do not measure, but that are fundamental to what it means to be human, are the ones that we are likely to need more of in the future. For example, empathy, love and compassion. If I ask you to look at these pictures – what do you feel?

In the words of Yuval Noah Harare from 21 Lessons for the 21stCentury: …” if you want to know the truth about the universe, about the meaning of life, and about your own identity, the best place to start is by observing suffering and exploring what it is.”

What AI can or will ever be able to do this? It is important that we ensure that we still can.

And now, if we look at these pictures – again, I ask you what do you feel? How do those feelings impact upon the way you might behave? We undervalue these aspects of humanity when it comes to our evaluations of intelligence, and yet I would suggest that it is our human emotional and meta intelligence that enables us to feel horror at human suffering and pleasure at human love.

The holistic set of interwoven intelligence enables us to be human and AI can help us to both develop the sophistication of our intelligence, across all its elements, and it will also help us to assess, and yes, to measure much of this. If that is what we want to do. What we need is good data, and smart AI algorithms that have been designed in a way that is informed by what we know about how humans learn.

We can collect data from a vast array of sources these days. We can collect it as people interact in the world, even when they do not realise, they are interacting with technology. We are no-longer simply restricted to collecting data explicitly through the interfaces of our desktop, laptop, tablet and smart phone technologies. We can collect it through observation, wearable technology and facial recognition.

For example, in research conducted at the Knowledge Lab with my colleague Dr Mutlu Cukurova, we collected a range of data in our attempts to understand how we could identify signifiers of collaborative problem-solving efficacy that would be susceptible to AI collection and analysis. As you can see from this visualisation of all the data sources, we were able to capture, it is complex and does not tell us anything of great interest.

However, by using learning from the social sciences that provides evidence that factors, such as the synchrony of individual group members’ behaviours can signify positive collaborative behaviours. We can then inform the design of the AI algorithms that we use to process this data. We therefore analysed the eye tracking and hand movement data that we collected through this research test rig. We found that there was indeed a greater instance of synchrony of eye gaze and hand movements between different members of a group, when that group was behaving in a positively collaborative manner, as assessed by an independent expert.

This is just one example of a small signifier, but when combined with a battery of other detailed signifiers, we can start to generate accurate and nuanced accounts of what is happening as people learn. Accounts that can be extremely useful to teachers and learners. AI can help us to track and support the development of our human intelligence in very sophisticated ways.

But, what does this mean for teaching?

Numeracy and literacy, including data literacy, will of course remain fundamental to all education, as will the basics of AI;

Emphasis for the remaining subject areas needs to be on what these subjects are, how they have arisen, why they exist, how to learn them and how to apply them to solve complex interdisciplinary problems;

Debate and Collaborative Problem Solving provide powerful ways to help students understand their relationships to knowledge and to hone their ability to challenge and question;

To ensure that teachers and trainers have the time to work with their students and trainees to develop these complex skills, we can use AI to:

Provide tutoring for numeracy, literacy (including data literacy) and basic subject knowledge;

We then blend this with our human-intelligent teachers who can refine this understanding through activities such as debate and collaborative problem solving; and to develop learners’ social and meta intelligence (meta-cognitive, meta subjective, meta contextual and accurate perceived self-efficacy);

And then the finesse to this piece – we use the AI to analyse learner and learning data, so that teachers know when to provide optimal support and learners get to know themselves more effectively.

I find that decision makers in education are very risk averse and often do not want to make big changes, because they are concerned that such changes might disadvantage the people in the process of their education when the change hits. I can understand this. However, if we do not make big changes the consequences are likely to be worse, and the risks much greater. As the FT expressed this in 2017:

“The risk is that the education system will be churning out humans who are no more than second-rate computers, so if the focus of education continues to be on transferring explicit knowledge across the generations, we will be in trouble.” (Financial Times 2017).

This would be a retrograde step indeed and would take us back to the first instances of robots, as seen here in this image from a play by Czech writer Karel Čapek who introduced the word robot in 1920 to describe a race of artificial humans in a futurist dystopia.

To sum things up as we draw to a close: We need to make these three things happen: Use AI to tackle educational challenges, prioritize the development of our uniquely human intelligence, educate people about AI. To do this we need partnerships between educational stakeholders to build capacity.

Partnerships of the type that we build through the EDUCATE programme. These partnerships are to generate the golden triangle that is the foundation of impactful high-quality educational technology (including AI) design and application. The idea of the Golden Triangle formed at a meeting in January 2012 when I was talking with my research colleagues Mike Sharples and Richard Noss, along with Clare Riley from Microsoft and Dominic Savage from BESA – we had met up with some educators and were puzzling about why the UK Educational Technology business was not better connected to researchers and educators. This was the birth of the triangle: the points of which are the EdTech developers, the researchers and the educators – all of whom need to be brought together to develop and apply the best that technology can provide for education.

The triangle is golden, because it is grounded in data. It is a tringle, because it connects the three key communities: the people who use the technology, the people who build the technology and the people who know how to evidence the efficacy of the technology for learning and/or teaching.

This golden triangle is at the heart of what needs to be done for AI to be designed and used for education in ways that will support our educational needs. It is the triangle at the heart of the partnerships that engage the AI developers, most of whom do not understand learning or teaching, with the educators, most of whom do not understand AI, and the researchers who understand AI and learning and teaching. It is the co-design partnership that will drive better AI for use in education, more educated educators who can drive the changes to the way we teach and learn that are required for the fourth industrial revolution and also help their students understand AI, and more educationally savvy AI developers

The Reality and the Potential of AI is that:

AI is smart, but humans are and can be way smarter.

There are 3 ways AI can enhance Learning and Teaching

- Tackle Educational Challenges using AI;

- Prioritize Human Intelligence;

- Educate people about AI: Attention to Ethical AI for Education is essential;

Partnerships are the only way we can achieve this.

Many thanks for coming to hear me speak this evening. I hope that I have piqued your curiosity and that you will have many questions to ask me.