This evening Nesta launched their report: Decoding Learning, which was authored by the London Knowledge lab and colleagues at LSRI in Nottingham.

This evening Nesta launched their report: Decoding Learning, which was authored by the London Knowledge lab and colleagues at LSRI in Nottingham.

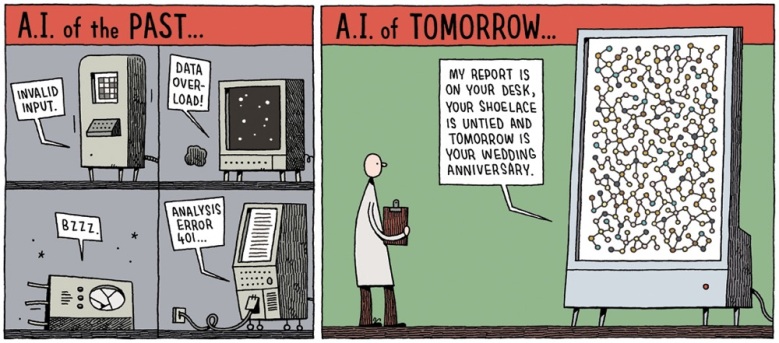

Our starting point for the research we report was that digital technologies do offer opportunities for innovation that can positively transform teaching and learning, and that our challenge is to identify the shape that these innovations take.

Many research studies have addressed the impact of particular technological innovations, and many meta–analytic reviews have aggregated these findings. Typically, these synthesising reviews do find some evidence of positive impact. However, there are two important complicating factors that limit the strength of the claims that can be made.

Firstly, the evidence is drawn from a huge variety of learning contexts: the wide range of teacher experience and learner ability means that too often the impact identified is relatively modest in scale. The breadth of contexts limits the impact.

Secondly, these findings are invariably drawn from evidence about how technology supports existing teaching and learning practices, rather than transforming those practices.

We looked for proof, potential and promise in digital education:

Proof by putting the learning first.

Promise for technology to help learning in new ways.

Potential to make better use of technologies we already have.

In order to ask these questions we need to look beyond the published research and corporate publications, we need to look at what is happening amongst teachers and learners as well.

What is clear is that no technology has an impact on learning in its own right; rather, its impact depends upon the way in which it is used. Accordingly, we have organised our review around 8 effective learning themes, which are based upon an analysis of learners’ actions.

In each theme there are reasons to feel positive and reason to want more – there are some great examples in this report from traditional technologies such as:

- Interactive White Boards being used in effective ways, to

- Learners working with experts to identify solar storms, to

- Using context-rich life-logs to increase their understanding of their own learning and capability and

- teachers creating GPS games that meet the learning needs of their students.

It is important to recognise that in addition to the learning themes themselves, which incorporate a variety of learning activities; the learning themes can be combined in interesting and effective ways– for example, the suite of web-based learning tools that was used in one of our highly rated teacher-led examples illustrates one example of Learning in and across Settings providing an overarching framework for Learning through Making. Small groups of learners were taught web design using collaboration scripts and incomplete concept maps. These tools were designed to allow groups of learners to work together on extended tasks using a scripted inquiry approach. The cross-setting opportunities created by the online environment allow classroom support for construction projects that mainly occur at home.

It is important to recognise that in addition to the learning themes themselves, which incorporate a variety of learning activities; the learning themes can be combined in interesting and effective ways– for example, the suite of web-based learning tools that was used in one of our highly rated teacher-led examples illustrates one example of Learning in and across Settings providing an overarching framework for Learning through Making. Small groups of learners were taught web design using collaboration scripts and incomplete concept maps. These tools were designed to allow groups of learners to work together on extended tasks using a scripted inquiry approach. The cross-setting opportunities created by the online environment allow classroom support for construction projects that mainly occur at home.

BUT Understanding how technology can be employed to improve learning is only part of the picture.

If innovations are to enter the mainstream, and if they are to fulfil their obvious potential, there are a number of systemic challenges that must be addressed.

We have identified certain trends and opportunities grounded in effective practice and set out what we believe are the most compelling opportunities to improve learning through technology.

For example, there is too little innovative technology-supported practice in the critical area of Learning from Assessment. And yet huge potential through learning analytics and a growing appetite for formative assessment. If, as learners, we do not know what we understand then how can we progress? If, as teacher, we do not know what our students understand, how can we help them to learn?

Making is an effective way of learning. There is much excitement around mending, mashing, and making with digital tools, making it an area ripe with possibility. Robotic kits, authoring tools, and multimedia production tools are just some examples of the technologies that can support learning through making. To learn effectively through making, careful consideration needs to be given to how the process of making leads to the desired learning outcome and to the sharing that is a vital component of learning through construction

What more might we gain by combining these two themes and conducting formative assessment through making and sharing?

All these examples, highlight the fact that Innovation needs to be conceptualised as some learning with a technology used in a particular way in a particular context.

1) We must stop talking about technology generically without being more specific – what technology, how used to support what type if learning, where, with whom and with what else?

To not recognize this is to reduce the value of the question to asking if roads are an effective ay of getting from a to b – of course roads can get me from a to be, BUT which road, what time of day, who else is driving, what are the weather conditions? Will it be faster than the train – well it depends….

… And travel is so much simpler than learning

So, – Ask rather can games help make the drill and practice activities effective for learners on their own at school? Sure, they can if they are well designed and challenge the child appropriately addressing explicitly what needs to be learnt and offering appropriate support.

Can digital making and mobiles help learners understand more about how energy consumption in their home changes over time and according to their household’s behaviour – well sure it can if they use some sensors for temperature and light, arduino technology and data reporting to an online aggregator, such as cosmo.com for example, and then present and access this through a bespoke mobile phone application that you build yourself and that you can use to check the family consumption while you are travelling home from school on the bus

Can digital making and mobiles help learners understand more about how energy consumption in their home changes over time and according to their household’s behaviour – well sure it can if they use some sensors for temperature and light, arduino technology and data reporting to an online aggregator, such as cosmo.com for example, and then present and access this through a bespoke mobile phone application that you build yourself and that you can use to check the family consumption while you are travelling home from school on the bus

…And these technologies are inexpensive

Ask the right question and you’ll get a useful answer

2) We need to take more notice of practice and better link this to academic research.

We need to think again about how this type if evidence can be more effectively brought into the picture – can we use technology to create the kind of database of examples that can start to provide a more ‘scientific’ evidence base for us ot use?

3) New pedagogy? or old pedagogy in a new frock?

If you really want to change pedagogy then stop JUST collecting evidence about how to make existing pedagogy work with technology

4) We need to know more about what is happening when technology is used effectively.

We need better evidence about the context in which technology is being used effectively.Evidence about the impact of technology on teaching and learning is gathered from a huge variety of learning settings, and reported without adequate indexing of the contextual factors that influence the nature and scale of the impact recorded. This means that applying the findings of any research study to a fresh setting is severely hampered. We need to know where, with whom, with what …

5) Make better use of what we have got

We need to change the mindset amongst teachers and learners: from a ‘plug and play’ approach where digital tools are used, often in isolation, for a single learning activity; to one of ‘think and link’ where those tools are used in conjunction with other resources where appropriate, for a variety of learning activities. Teachers have always been highly creative, creating a wide range of resources for learners. As new technologies become increasingly prevalent, they will increasingly need to be able to digitally ‘stick and glue’. To achieve this, teachers will need to develop and share ways of using new technologies – either through informal collaboration or formal professional development. But they cannot be expected to do this alone. They need time and support from school leaders to explore the full potential of the technologies they have at their fingertips as tools for learning. School leaders can further assist teacher development by tapping into the expertise available in the wider community.

6) If you want better innovations, then Link industry, research and practice to realise the potential of digital education.

There is strong evidence of disconnect between the key partners involved in developing educational technology. This situation makes little sense at a time when technology has become consumerised across society, and there is increasing evidence for the efficacy of technology as a learning tool. Academic and practitioner research is poorly connected and is typically conducted in isolation from the technology developers whose products grace our schools and homes. And yet, both researchers and the developers of educational technology need to know whether, and how, their work enhances learning. Industry, researchers and practitioners need to work closely together to test ideas and evaluate potential innovations at a time when design changes can easily be implemented and products can be improved before they are taken to market. Such a process would benefit industry by providing clearer evidence of effectiveness to boost sales; and it would benefit practitioners who would have access to better products on the market.