I am really delighted to be speaking at a fascinating event in Sydney, New South Wales where they are embracing the need to plan for the impact of AI in Education. The symposium is part of the Education for a Changing World project of the NSW Department of Education that is examining the implications that advances in technology will have for education. The project aims to stimulate informed discussions about how we should be preparing children to thrive in an increasingly complex and interconnected world.

The project’s first discussion paper explores some of the department’s initial thinking about the challenges of the big technological, economic, demographic and social shifts occurring around the globe. In addition to which, the department has established the Education: Future Frontiers Occasional Paper Series to widen the evidence base and the case for change. The paper I contributed is published here below:

Occasional Paper: The implications of Artificial Intelligence for teachers and schooling

Rose Luckin, Professor of Learning with Digital Technologies, University College London Institute of Education’s Knowledge Lab

Most people in countries where modern technology is widely used will be interacting with Artificial Intelligence (AI) through its many practical applications in computers that have visual capabilities, that can learn, solve problems, make plans, and understand and produce natural language, both spoken and written. These AI applications are used in areas such as medical diagnosis, language translation, face recognition, autonomous vehicle design and robotics.

AI is also already being applied to educational settings. For example Alelo has been developing culture and language learning products since 2005 and specialises in experiential digital learning driven by virtual role play simulations powered by AI. Carnegie Learning produce the software that can support students with their mathematics and Spanish studies. In order to provide individually tailored support for each learner the software must continually assess each student’s progress. The assessment process is underpinned by an AI-enabled computer model of the mental processes that produce successful and near-successful student performance.

UK-based Century Tech, has developed a learning platform with input from neuroscientists that track students’ interactions, from every mouse movement and each keystroke. Century’s AI looks for patterns and correlations in the data from the student, their year group, and their school to offer a personalised learning journey for the student. It also provides teachers with a dashboard, giving them a real-time snapshot of the learning status of every child in their class.

These examples merely scratch the surface of what is possible with AI. The purpose of this paper is to explore how AI is relevant to education and what AI can contribute to teaching and learning to help students and educators progress their understanding and knowledge more effectively.

The relevance of AI to education

In order to benefit from the potential advantages of AI – from personalised cancer treatment specified according to individual genetic profiles generated by AI to workplace automation that increases productivity – we must attend to the needs of education as a matter of urgency.

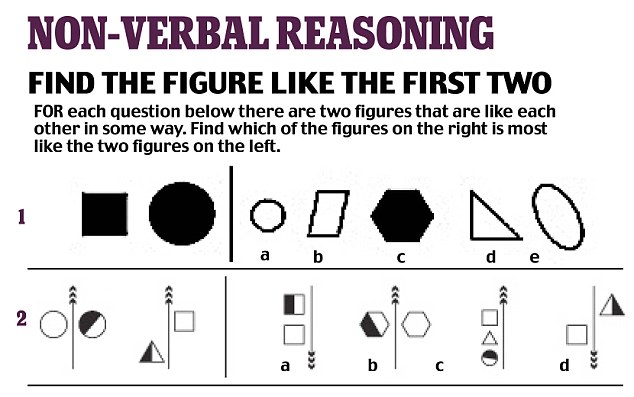

To be blunt, none of the potential AI benefits will be achieved at scale unless we address education and AI now. The nature of what needs to be done is summarised in Figure 1, which illustrates the elements involved in the AI and education knowledge tree. There are two key dimensions that need to be addressed:

- How can AI improve education and help us to address some of the big challenges we face?

- How do we educate people about AI, so that they can benefit from AI?

This paper will examine both of these dimensions in turn.

Figure 1: The AI and Education Knowledge Tree

Dimension 1. Addressing educational challenges with AI

The thoughtful design of AI approaches to educational challenges has the potential to provide significant benefits to educators, learners, parents and managers. But it must not start with the technology, it must start with a thorough exploration of the educational problem to be tackled.

A clear specification of the problem provides the basis on which a well-designed solution can be developed. Only when a solution design exists, can we start to consider what role AI can best play in that solution and what type of AI method, technique or technology should be used within that solution. There is an obvious and important role for teachers in the pursuit of a problem specification and solution design. Without this enterprise, the technologists cannot design effective AI solutions to the key educational challenges recognised across the globe.

Identifying the problem

For the purposes of this paper, I’ll take the definition of AI used in the Oxford dictionary, which defines AI as: computer systems that have been designed to interact with the world through capabilities (for example, visual perception and speech recognition) and intelligent behaviours (for example, assessing the available information and then taking the most sensible action to achieve a stated goal) that we would think of as essentially human.

AI is an interdisciplinary area of study that includes psychology, philosophy, linguistics, computer science and neuroscience. The study of AI is complex and the disciplines are interlinked as we strive for a greater understanding of human intelligence as well as attempting to build smart computer technology that behaves intelligently.

A key aspect of this definition that is often overlooked is the initial statement about an AI being a computer system that has been designed to interact with the world in ways we think of as human and intelligent. In current discussions of AI in the media, for example, we tend to focus on the AI technology rather than the problem and the design process that has preceded and informed the implementation of the AI technology. This is ironic, because the most important aspect of AI is the identification of the problem to which intelligence is to be applied and the design of a clear understanding and representation of that problem.

Without this problem specification process, there is no chance of developing a good solution to which AI technology can be applied. The AI designer must have a good understanding of the problem AI is supposed to solve, as well as the type of AI technique that might be appropriate. The features of the problem must be specified along with the features of the environment in which the AI must operate. Once we recognise the importance of the AI design stage we can start to unpack the relevance of AI to teaching and learning and the vital role that educators need to play if AI is to meet its potential in the benefits it can provide to education.

I remember when I was an undergraduate studying AI, one of the hardest final year examinations was a paper that we could complete outside normal exam conditions over a three-day period. The paper presented candidates with a selection of problems. For example: a complex of road junctions where fluctuating traffic flow rates and poor visibility had resulted in a series of accidents, or a teacher who needed to provide support for a class of language learning students who were all at very different levels of proficiency.

As students we were required to select one of the problems, describe the problem as we understood it including any assumptions we were making, develop a potential solution and design the AI techniques and technologies that could be used to implement our proposed solution. The first example problem requires predominantly a planning or possibly a computer vision approach, whereas the second is more likely to be concerned with knowledge collation and representation, possibly also knowledge elicitation. Students were not required to implement any technology or write any code; the paper was designed to test their design skills.

My point here then is that when we ask how AI can contribute to teaching and learning, we need to start from the problems that we believe need to be tackled.

Designing solutions

Thinking about the problem specification and solution design stage of AI should prompt us to start considering how AI could help us to transform problematic educational activities and bring about changes to the working lives of teachers. Changes that would make best use of teachers’ uniquely human skills and abilities, and that would remove much of teachers’ routine administration, record keeping and assessment work.

Before looking at examples of the changes that could be made to the job of being a teacher, it is important to consider briefly the changes to the workforce that are likely to occur, partly due to the automation brought about by AI. Schools will need to ensure that they equip students to be effective in the future workforce and educators will therefore need to know which skills, abilities and knowledge are most valuable for their students to learn.

The impact of technology, particularly automation, on employment is a key topic of debate at the moment in much of the western world. Predictions about the future pace of technological change, due to AI have historically been over-optimistic. In fact, the jobs and skills composition of a workforce have tended to change only gradually over time.[1] The most dramatic historical shift was from agriculture to industry rather than due to an ICT-driven transformation. Current estimates of the impact of future automation on the number of jobs and the types of jobs most at risk vary. See Marc Tucker’s essay Educating for a digital future – the challenge as part of this series for detailed consideration of these issues.

Some jobs are more likely to be augmented by AI rather than replaced through the automation of specific tasks. For example, lawyers routinely conduct document reviews, which is a task that can be automated in some contexts. However, lawyers also provide advice to their clients and complete negotiations for their clients and these tasks are much harder to automate. Not only does this suggest that there is not a clear one-to-one relationship between a job lost and a task automated, but also that the coordination of the different tasks between machines and humans may be a new job in its own right. The situation is made more complex by the many factors at play beyond automation: globalisation, environmental sustainability, urbanisation, increasing inequality, political uncertainty for example.

The only thing we can be sure about is that the future workplace will be uncertain, unpredictable and that our students will therefore need to be able to cope with this uncertainty, to be resilient, flexible and lifelong learners. The way to achieve this is to focus on individuals as learners and enable them to be effective for themselves and with and for others and society too.

The key skill people will need for their future work lives will be self-efficacy – by this I mean that every individual needs to have an evidence-based and accurate belief in their ability to succeed in specific situations and to accomplish tasks both alone and with others. A person’s sense of self-efficacy plays a key role in how people tackle tasks and challenges, and how they set their goals, both as individuals and as collaborators. It is something that can be taught and mentored and it requires an extremely good knowledge of what one does and does not know, what one is and is not so good at, where one needs help and how to get this help. This self-knowledge is not just about subject specific knowledge and understanding, but also about one’s wellbeing, emotional strength and intelligence.

This self-knowledge and efficacy is particularly important because these are skills that AI cannot replicate. No AI developed to date understands itself, no AI has the human capability for metacognitive awareness and self-knowledge. We must therefore ensure that we develop our knowledge and skills to take advantage of what is uniquely human and use AI wisely to do what it does best: the routine cognitive and mechanical skills that we have spent decades instilling in learners and testing in order to award qualifications.

The implications of this for school systems, the curriculum and teaching are profound and educators must engage in discussing what needs to change as a matter of urgency. This is not a job for the technologists, but if we do not motivate educators to engage in discussions about what AI could and should be used for in education the large technology companies may usurp the educators and occupy the AI vacuum that a lack of engagement will produce.

Leveraging AI to enhance teaching and learning

What I hope is clear from the discussion about the future of the workforce is that we need to review what and how we teach and ensure that AI is designed and used as a tool to make our students (and ourselves) smarter, not as a technology that takes over human roles and dumbs us down. To achieve this we need to concentrate on developing teaching and schooling that develops the uniquely human abilities of our students as well as instilling within them the requisite subject knowledge in a flexible, interdisciplinary and accessible manner.

The parallel in teaching is that we need AI assistants to relieve teachers from the routine automatable parts of their job and enable them to focus on the human communication, the sensitive scaffolding and supporting the wellbeing of their students so that they can build the self-knowledge and self-efficacy that will ensure that they are able to advance in their chosen workplace.

Three examples of the ways in which teaching and schooling could be re-imagined are presented below, each is driven by a significant educational challenge.

Example 1: Assessing what can’t be automated not what we can easily automate

The current outdated assessment systems that prevail across the world revolve around testing and examining the routine cognitive subject knowledge that can easily be automated. These assessment systems are also ineffective, time consuming and the cause of great anxiety for learners, parents and teachers. However, there is now an alternative due to the potential information we can gain from combining big data and AI and applying it to the problem of assessing learning. There is a rather beautiful irony in the fact that while unable to understand itself or develop any self-knowledge, AI can help us to understand ourselves as learners, teachers and workers.

Let me explain what I mean by this:

- The careful collection, collation and analysis of the data that can be harvested through people’s use of technology gives us a rich source of evidence about how learners are progressing, cognitively, metacognitively and emotionally;

- Continuing work in psychology, neuroscience and education has increased our understanding of how humans learn. This increased knowledge can be used to specify signifiers or behaviours that evidence learner progress;

- Our increased knowledge about human learning can also be used to design AI algorithms and models that can analyse data about learners, recognise signifiers of learning and build dynamic models of each individual students’ progress holistically so that we can chart their development of self-knowledge and self-efficacy as well as their increased knowledge and understanding of key subject knowledge;

- The final step in the process is to design ways in which we can visualise the data that has been analysed to define each learner’s progress cognitively, metacognitively and emotionally. These visualisations can be used by learners, educators, parents and managers to understand the detailed needs of each learner and to develop within each learners the skills and abilities that will enable them to be effective learners throughout their lives.

An AI assessment system that was composed of these AI tools and that illustrated to every learner the analysis of their progress in an accessible format would support learning and teaching through continually assessing learning of both subject specific knowledge and the skills and capabilities that the AI augmented workforce will require, such as negotiation, communication and collaborative problem solving.

This AI assessment system would be more accurate and cheaper than the human intensive examination systems currently in place and it would free up time for teaching and learning that is currently taken up when we stop teaching in order for people to sit tests and exams. Assessment would happen continuously while people learn. This assessment change requires political will as well as investment in technology development and engagement with teachers, students and parents so that they fully understand the AI assessment proposition.[2]

Example 2: Addressing the achievement gap between advantaged and disadvantaged learners

AI could also help to make the education system more equitable. Education is the key to changing people’s lives but the less able and poorer students in society are generally least well served by education systems. Wealthier families can afford to pay for the coaching and tutoring that can help students access the best schools and pass those currently cherished exams.

AI would provide a fairer assessment system that would evaluate students across a longer period of time and from an evidence-based, value-added perspective. It would not be possible for students to be coached specifically for an AI assessment, because the assessment would be happening in the background, over time, without necessarily being obvious to the student. AI assessment systems would, for example, be able to demonstrate how a student deals with challenging subject matter, how they persevere and how quickly they learn when given appropriate support.

One of the key benefits that AI can bring to all learners is the capability to understand more about themselves: what they know and where they need help to understand, their strengths and weaknesses and their well-being. Metacognitive awareness is a complex concept, but broadly it refers to any knowledge or cognitive process that references, monitors or controls any aspect of cognition. Scholars distinguish between a person’s knowledge of their cognitive processes and the processes they use to monitor and regulate their cognition. This latter regulatory process incorporates a variety of executive functions and strategies, such as planning, resource allocation, monitoring, checking and error detection and correction.

Good metacognitive awareness and regulation enhances cognitive performance, including attention, problem-solving and intelligence and it has been shown to increase learning outcomes[3]. Successful students continually evaluate, plan and regulate their progress, which makes them aware of their own learning and promotes deep-level processing. Metacognitive awareness and regulation can be taught and supported, and can benefit learners of all abilities.

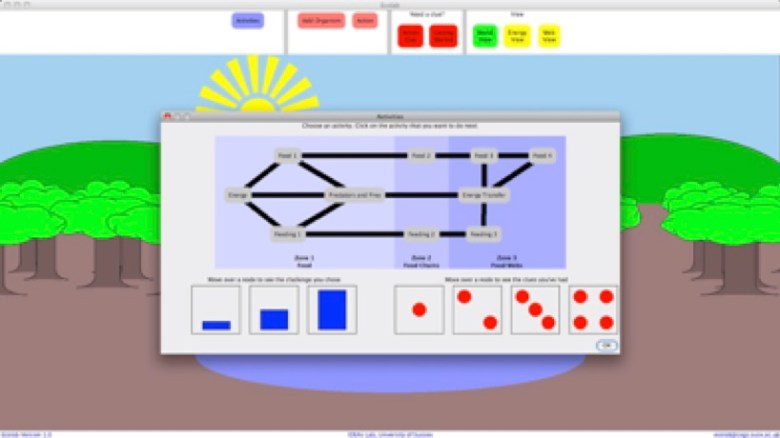

A series of studies we conducted using an AI software simulation called the Ecolab demonstrated that AI could be employed to scaffold learners to develop metacognitive skills, in particular help seeking and task difficulty selection skills. [4] The results demonstrated that the students whose subject knowledge and ability had been assessed as being below average gained particular benefit and performed significantly better than more-able students, who also performed well.

In addition to employing AI to scaffold the development of these important learning skills, we can also use AI to visualise to students the trajectory of their progress and increase their self-awareness. For example, in Figure 2, the map in the dialogue box entitled ‘Activities’ depicts the area of the curriculum that the child is studying, with each node representing a curriculum topic. When the user clicks on a node in this map, the bar chart below and to the left of the map indicates the level of difficulty of the work that the child has completed while working on this topic, and the dots on the ‘dice’ below and to the right of the map indicate how much help the child has received.

Figure 2 An example of a visualisation of student performance, courtesy of Ecolab

Example 3: Making teaching more effective

Imagine a classroom setting ten years hence where data about each learner’s movements, speech and facial expressions are automatically logged by passive capture devices within the fabric of the classroom. This information is combined with data about each learner’s performance recorded by the school’s assessment system, and by data input from teacher, parent and the learner themselves. All this data is used to update the class teacher’s pupil records and to provide data for an AI-based teaching assistant that keeps track of every learner’s progress: cognitive, emotional and metacognitive.

The AI teaching assistant relieves the teacher of all record keeping and recording activities and is able to provide up to the minute information about any pupil through a teacher activated speech based interface or through a software application. Teachers can also ask their AI assistant to identify an appropriate tutoring application, like those described at the start of this paper, for a group of students who need particular support with an area of the curriculum. The AI assistant can search for resources or media to meet the teacher’s requirements for the day, or it can identify and contact local entrepreneurs who are willing to come and talk to pupils about future work opportunities or how to be an entrepreneur.

The possibilities for the AI assistant are vast and encompass all the routine, data intensive and time consuming activities that are essential to the smooth running of the classroom, but that don’t need the expertise of a teacher. This allows the teacher to focus on the process of teaching and learning ensuring that all pupils benefit from the unique human skills involved in effective intersubjective teaching and learning interactions.

There are more than 30 years of research on AI for education that demonstrate that we can use AI to make teaching more effective and more economical by augmenting teachers with AI systems so that teachers can concentrate on the teaching activities that require the general and specialist intelligence that AI does not (yet?) have. The outputs from this research are now required to build the AI teaching assistants that schools and universities need, such as that described here. We have the technology know how, we now need the initiative to make such assistants a reality. This initiative would need to engage educators across the sectors to help ensure that the capabilities of AI assistants address the requirements of their teaching realities.

Dimension 2. Education about AI

There are three key elements that need to be introduced into the curriculum at different stages of education from early years through to adult education and beyond if we are to prepare people to gain the greatest benefit from what AI has to offer.

The first is that everyone needs to understand enough about AI to be able to work with AI systems effectively so that AI and human intelligence (HI) augment each other and we benefit from a symbiotic relationship between the two. For example, people need to understand that AI is as much about the key specification of a particular problem and the careful design of a solution as it is about the selection of particular AI methods and technologies to use as part of that problem’s solution.

The second is that everyone needs to be involved in a discussion about what AI should and should not be designed to do. Some people need to be trained to tackle the ethics of AI in depth and help decision makers to make appropriate decisions about how AI is going to impact on the world.

Thirdly, some people also need to know enough about AI to build the next generation of AI systems.

In addition to the AI specific skills, knowledge and understanding that need to be integrated into education in schools, colleges, universities and the workplace, there are several other important skills that will be of value in the AI augmented workplace. These skills are a subset of those skills that are often referred to as 21st century skills and they will enable an individual to be an effective lifelong learner and to collaborate to solve problems with both Artificial and Human intelligences.

I have already discussed the importance of both metacognition and self-efficacy. Here I therefore simply note that these two concepts are inter-linked and essential for lifelong learning. Collaborative problem solving brings together thinking about the separate topics of collaboration and problem solving, each with their own research history. Collaborative problem solving is a key skill for the workplace, and its importance is only likely to grow as further automation takes effect.

There is a mismatch between the substantial evidence in favour of collaborative problem solving and learning reported in the literature and the approaches widely used within schools. This is neither preparing students for university nor the workplace. For example, in an interview for a Davos 2016 debate on the Future of Education, a student from Hong Kong stated that the current school system produced: “industrialised mass-produced exam geniuses who excel in examinations” but who are “easily shattered when they face challenges”. We need employees to be able to tackle challenges and this often involves working effectively with others to solve the problem at the heart of any challenge; we don’t need exam geniuses who crumble under the pressure of the real world.

Collaborative problem solving does not happen spontaneously. Both teachers and students require a high level of training to employ collaborative problem solving effectively, and yet there is little evidence of concerted training effort. This means that when teachers do attempt to employ collaborative problem solving, the quality of the group interactions and dialogue can be poor.

It is extremely difficult to isolate the precise nature of the key factors that impact on the effectiveness, or not, of collaborative problem solving. We can, however, identify factors that are frequently mentioned as being influential upon success. These factors include: the environment in which collaborative problem solving takes place; the composition, stability and size of the group and their problem solving and social skills, and teacher training.

To be effective at collaborative problem solving, people need to be able to:

- articulate, clarify and explain their thinking;

- re-structure, clarify and in the process strengthen their own understanding and ideas to develop their awareness of what they know and what they do not know

- adjust their explanations when presenting their thinking, which requires that they can also estimate others’ understandings;

- listen to ideas and explanations from others – this may lead listeners to develop understanding in areas that are missing from their own knowledge;

- elaborate and internalise their new understanding as they process the ideas they hear about from others;

- actively engage in the construction of ideas and thinking as part of the co-construction of understandings and solutions;

- resolve conflicts and respond to challenges by providing complex explanations, counter evidence and counter arguments; and

- search for new information to resolve the internal cognitive conflict that arises from discrepancies in the conceptual understanding of others.

Implications for teacher training and professional development

The significant educational implications that AI brings to society, both when AI is viewed as a tool to enhance teaching and learning and when AI is viewed as a subject that must be addressed in the curriculum, make clear that teacher training and teacher professional development must be reviewed and updated.

If teachers are to prepare young people for the new world of work, and if teachers are to prime and excite young people to engage with careers designing and building our future AI ecosystems, then someone must train the teachers and trainers and prepare them for their future workplace and its students’ needs. This is a role for policy makers, in collaboration with the organisations who govern and manage the different teacher development systems and training protocols across countries. If the need for young people to be equipped with a knowledge about AI is urgent, then the need for educators to be similarly equipped is critical and imperative.

On a more positive note, the development of AI teaching assistants will provide an opportunity for developing deeper teaching skills and enriching the teaching profession. This deepening of teacher expertise might be at the subject knowledge level, or it could be concerned with developing the requisite skills to support and nurture collaborative problem solving in our students. It could also result in teachers developing the data science and learning science skills that enable them to gain greater insights from the increasingly available array of data about students’ learning.

Any failure to recognise and address the urgent and critical teaching and training requirements precipitated by the advancement and growth of AI is likely to result in a failure to galvanise the prosperity that should accompany the AI revolution. In particular, I see three major areas of concern:

- failure to recognise the importance of self-efficacy, because we are only measuring subject knowledge;

- failure to exploit the power of AI through fear of the security, privacy and protection of our personal data and that of our children; and

- failure to teach people enough about AI to empower them to make key decisions about what it should and should not, could and could not, will and will not be able to do for society.

Conclusions: the implications of AI for education

In this paper I have highlighted the need to see AI as more than particular technologies, such as machine learning, neural networks, or deep learning algorithms. For education to benefit from the potential of AI, we must focus on the problem specification and solution design elements of AI.

A key action for all of us must be to develop a culture of problem specification that encourages people to unpack educational problems, so that solutions that benefit from the symbiosis of AI and HI can be developed.

We need to start developing a curriculum and a pedagogy to ensure that our students develop the self-efficacy that will set them aside from their AI peers and that will help them to deal effectively with the changing and perhaps turbulent workplace of the future.

There is also great scope to reimagine teaching and schooling through the development of AI augmented teaching practices. This means that educators must ensure that their voices are heard by the technology companies that are developing their particular technology classrooms of the future. Early progress might easily address the administrative and routine tasks that currently take too much teacher time.

In addition there are social, technical and political challenges that also require our attention. Socially, we need to engage teachers, learners, parents and other education stakeholders to work with scientists and policy makers to develop the ethical framework within which AI assessment can thrive and bring benefit. Technically, we need to build international collaborations between academic and commercial enterprise to develop the scaled up AI assessment systems that can deliver a new generation of exam-free assessment. Politically, we need leaders to recognise the possibilities that AI can bring to drive forward much needed educational transformation within tightening budgetary constraints. Initiatives on these three fronts will require financial support from governments and private enterprise working together.

AI has the potential to bring about enormous beneficial change in education, but only if we use our human intelligence to design the best solutions to the most pressing educational problems.

Case study: AI and teacher shortages (note: to appear in body of paper or at the end, depending on layout requirements)

One of the big problems that we need to address in education is the global shortage of teachers. The UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) has estimated that in order to ensure inclusive and equitable quality primary and secondary education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all, countries must recruit 68.8 million teachers by 2030.[5] To put this in perspective, the total number of newly qualified teachers in England for the year 2016-2017 is 73,636[6] and for 2015, the number of students completing undergraduate and postgraduate ITE programs in NSW was 5,547 and across Australia the figure was 18,194.[7]

The temptation when faced with a problem such as global teacher shortages is to consider AI as a potential solution through the provision of AI rather than human teachers. There are however at least two significant reasons why this suggestion reflects a poor understanding of the problem. The full spectrum of teaching skills and abilities required of teachers is broad and complex. So while AI tutors may be able to provide tutoring in particular subject areas, AI is not (yet) able to fulfil the entire role of a human teacher.

A much more feasible approach would be through augmenting human teachers AI assistants in the classroom to help human teachers cope more effectively with their classes of students.[8] This could be an excellent way for AI to contribute to the teaching workforce. However, if we look at the problem again and unpick it a little, we see that a key part of the problem is not just the number of people who we need to become teachers, but also the lack of training and qualifications for these people.

The recognition that we need both more teachers and more training and qualification routes was the catalyst for a company called Third Space Learning, working in collaboration with the UCL Institute of Education’s Knowledge Lab, to develop the design for a system that will enable anyone who wants to teach to become a qualified online tutor. To be eligible people need to have a degree level qualification, some time to spare, and access to the internet. Each tutor will be trained online and will work on a one to one basis with learners from anywhere in the world, both within and outside schools and colleges.

So where is the AI in this design? The AI will be used to automatically evaluate the online human to human tutoring sessions to ensure quality standards are maintained. Evaluation is currently done by human evaluators and the cost of scaling-up this human resource approach are prohibitive. Initially, therefore our task has been to find identifiable signifiers or proxies for student learning within tutorial interactions. The list of dependent factors as proxies of student learning is extensive, however, three main themes emerge and are taken into account in defining best practice:

- the cognitive domain involving knowledge, understanding and skills about the studied content;

- the metacognitive domain involving the acquisition of knowledge and skills related to one’s own learning, in other words, the learners’ knowledge and understanding of their own learning;

- and the affective, often referred to as the emotional domain involving learners’ capacities to deal with their emotions, which effect their attitudes, locus of control, self-efficacy and interest etc.

We consider these three themes to be the core of a learner’s learning state: their susceptibility to learn. The theoretical background from these three themes provided an initial framework for the development of an annotation tool that could be used to score tutorial interactions. Informed by the framework we analysed past tutorial interactions and developed a mark-up language of successful tutorial interaction signifiers that can act as proxies for best practice. These proxies are integrated into an annotation tool that enables tutors to score or tag their sessions in real-time. The evidence from our evaluation of this annotation tool is being used to automate the tagging process using AI techniques. One particularly interesting finding from our early work is that real-time tagging is potentially more accurate than post session evaluation of tuition quality, because the latter are more vulnerable to a human evaluator’s bias.

The AI tool currently under development models the relationship between the inferences drawn from the tutorial interaction annotations, the actions that a tutor takes during those interactions and the performance of the student being tutored. In this way, we will automatically evaluate tutorial sessions according to the three core elements of learning: the cognitive, metacognitive and the emotional.

This AI evaluation process will also provide feedback for tutors and learners to improve their tutoring sessions. And it will provide the basis for personalised continuing professional development qualifications for the tutors, which is individualised according to each tutor’s performance as a tutor. Unpacking the problem of global teacher shortages this way maintains the role of the human as the teacher assisted and continually developed by AI.

[1] Handel, 2012 Handel MJ (2012) ‘Trends in Job Skill Demands in OECD Countries’, working paper 143, OECD. http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/ trends-in-job-skill-demands-in-oecd-countries_5k8zk8pcq6td-en

[2] For a more detailed account of this argument for AI assessment see http://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-016-0028

[3] See for example: Marzano, R. J. (1988) ‘Dimensions of thinking: A framework for curriculum and instruction.’ Alexandria VA: The Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

[4] Luckin, R. & du Boulay, B. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 26, 416–430 (2016).

[5] UNESCO. (2016). http://www.uis.unesco.org/Education/Documents/FS39-teachers-2016-en.pdf

[6]https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/572290/ITT_Census_1617_SFR_Final.pdf

[7] https://www.cese.nsw.gov.au/images/stories/PDF/Workforce_Profile_NSW_2015_FA7_AA.pdf

[8] https://howwegettonext.com/a-i-is-the-new-t-a-in-the-classroom-dedbe5b99e9e

There is a huge and growing interest among those who invest in new technology ventures, specifically Artificial Intelligence (AI) techniques and methods. For example, between 2011 and 16 May 2016 Sentient Technologies received over 143 million USD in funding (Data from

There is a huge and growing interest among those who invest in new technology ventures, specifically Artificial Intelligence (AI) techniques and methods. For example, between 2011 and 16 May 2016 Sentient Technologies received over 143 million USD in funding (Data from

of AI we need within education is the AI that enables the technology it powers to explain its reasoning, to justify its decisions and to negotiate with its users. This is the sort of AI technology that could help us address one of the toughest challenges within the current workplace: The lack of understanding about how humans can best work with AI systems so that the result is AI augmented human intelligence that is greater than the sum of its parts. We need workers who understand how to make the best use of the power that AI automation can bring to industry and commerce. Workers who understand enough about AI to know where and how human intelligence can work with AI to achieve a blended intelligence that can increase productivity. And what is beautiful about all this is that the appropriate type of AI can help us educate and train people to understand enough about their AI colleagues to work alongside them effectively.

of AI we need within education is the AI that enables the technology it powers to explain its reasoning, to justify its decisions and to negotiate with its users. This is the sort of AI technology that could help us address one of the toughest challenges within the current workplace: The lack of understanding about how humans can best work with AI systems so that the result is AI augmented human intelligence that is greater than the sum of its parts. We need workers who understand how to make the best use of the power that AI automation can bring to industry and commerce. Workers who understand enough about AI to know where and how human intelligence can work with AI to achieve a blended intelligence that can increase productivity. And what is beautiful about all this is that the appropriate type of AI can help us educate and train people to understand enough about their AI colleagues to work alongside them effectively.